Vanguard: The '60s Zine by Queer Homeless Youth

How gay street hustlers and a Methodist church fought for LGBTQ+ rights.

In the precarious times we find ourselves, a potent antidote for despair lies in the work that has already been done. As I dig deeper into the foundation that our queer elders have laid for us, I continue to find unexpected and miraculous surprises. One of the relics hiding in the dust is Vanguard, the United States’ first queer militant organization, that included a rag-tag group of young street hustlers, drag queens, transgender women, and Methodist pastors…

The Sixties, though heralded as a decade that welcomed expansiveness and exploration, was not a safe time to be queer. Being gay was illegal in nearly every state. Even San Fransisco, which was considered America’s gay mecca, saw openly queer people as young as thirteen violently beaten or killed in the streets. Police squads dedicated to rounding up queers in mass roamed the city, breaking ribs and routinely arresting citizens suspected of being homosexual. One could be arrested under the offense of “cross-dressing” for something as simple one’s blouse buttons being on the “wrong” side.

Most middle class queers were closeted, or flew under the radar within straight society, crossing their T’s and dotting their I’s so to not be found out. Those who were young runaways, poor, drag queens, people of color, transgender, and unable or uninterested in passing existed at the bottom of the food chain. As many as 90,000 queer people called San Francisco home in the Sixties, many of them lived in a fifty block radius known as the Tenderloin.

ten·der·loin: a district of a city where vice and police corruption are prominent.

The streets of the Tenderloin were crawling with young lonely wanderers, cast aside by their families, who came to the Bay looking for a home. Many sold their bodies, pushed drugs, stole, and did all they could to survive in a world that desired to see their elimination. Their work was dangerous, unpredictable, and many didn’t make it out alive. Adrian Ravarour, a young gay priest working in the Tenderloin, sought to change this.

Deeply disturbed by the police beating and harassment, Adrian drew from the teachings of civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. He encouraged queer street youth of all identities to organize, fight for their right to exist, and release any shame society had created around their queerness — in fact it was an identity to be celebrated. As their voice grew, their desire for action and organization followed suit. In 1965 Vanguard was officially born.

The first Vanguard handout read:

“The time is here to bring together the youth of the TENDERLOIN to form a more unified community among ourselves. We find that no one has room for us in their society, therefore we must work together to form our own society to meet our OWN needs. Our needs and goals are:

1) Coffee House and meeting center

2) Emergency Housing

3) Medical aid, area VD clinic, etc.

4) Employment counseling.

5) Police cooperation

6) Financial aid (if possible)

We are willing to work with interested groups, but, who can be more trusted and relied upon than ourselves. To find satisfaction we found one another.”

In August 1965 Adrian was connected with Albert Cecil Williams, the newly appointed senior pastor at Glide Memorial Church, to help host a safe place for Vanguard meetings. As one of the first Black Americans to be involved in gay liberation, Albert welcome the group, and the Glide church basement became a safe space for queer youth to commune and belong.

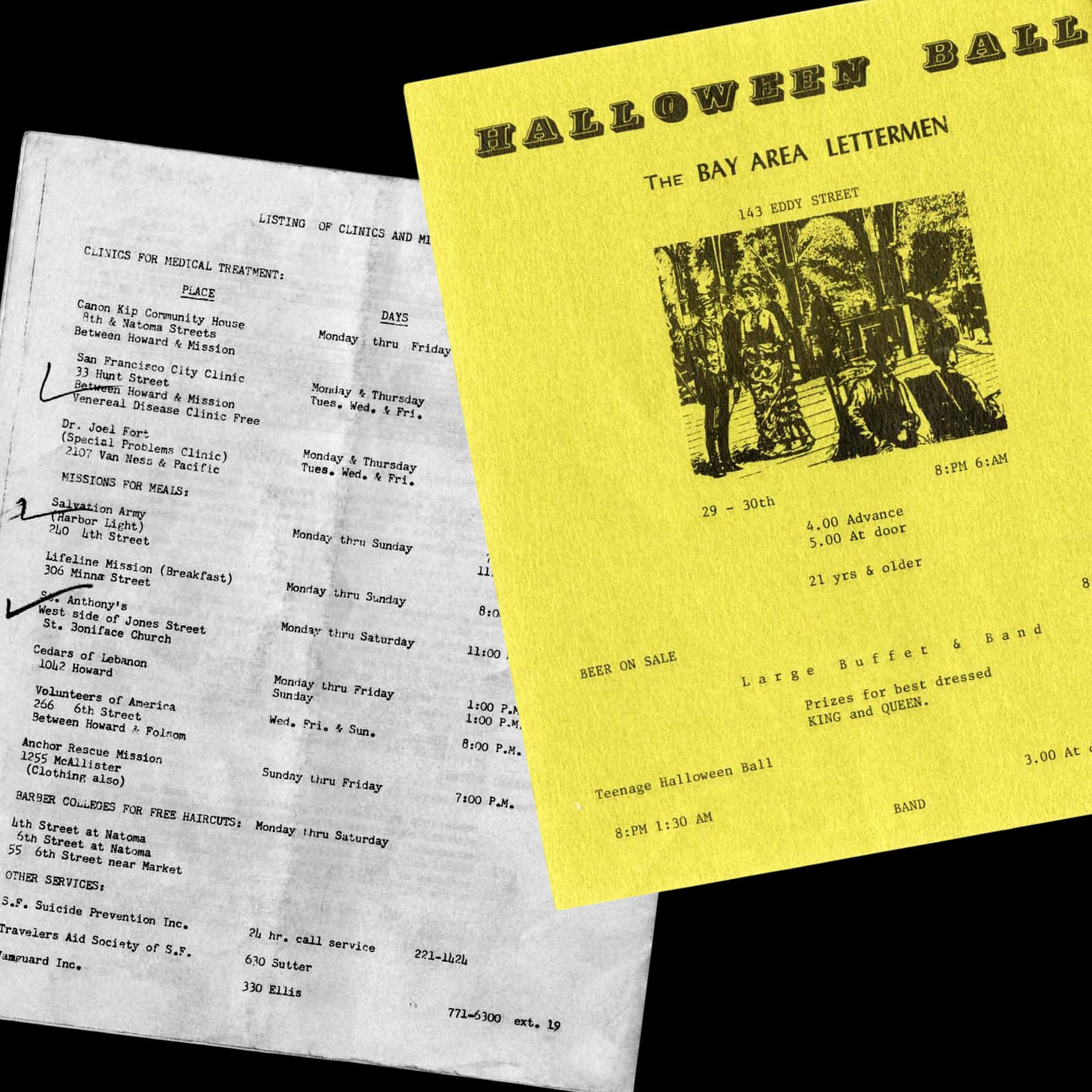

Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, the members of Vanguard aimed to participate in direct tactics to achieve liberation. From the church basement they organized free food and clothing distributions, hosted weekly gay dances and balls, and began distributing Vanguard Magazine throughout the city. The group of homeless youth drew members ranging from 15-35 years old. Their aim? To advocate for and celebrate the most disenfranchised members of gay society — the hustlers, transgenders, and drag queens.

“We were the only ones who would respond to the needs of these people… if you make yourself available to people, there’s got to be a complete commitment. A commitment just to help those it’s easy to help is hypocritical” - Albert Cecil Williams, Wall Street Journal, circa March 13, 1967

“Day after day I hear complaints about the prejudices that the straight society has against the gay society. Let’s look at our own prejudices. We are much more prejudiced about our own kind than the straights are! We ostracize people because they do this that or the other in bed. We make snide remarks about a drag queen who isn’t quite convincing enough. The “leather boys” are the butt of many jokes and much ridicule. Then there is the hair fairy.

If we want the majority of society to accept us as we are, we are going to have to start accepting ourselves and the others like us.

There are many organizations for homosexuals all over the country. Most of them have rules like: no drag, no hair fairies, etc. etc. This is fine in a legal situation, but why shouldn’t we take the chance of getting busted? These people are homosexual just like us. We all want unity, but no-one will fight to get it. As I said before: let’s start taking a good long look at our selves before we start tearing down somebody else.” - J.P Marat, President of Vanguard - Issue 2, circa 1966

All Trash Before the Broom - read the picket sign. It’s July 1966, and Vanguard has gathered 50 members for a tongue-in-cheek protest designed to highlight the hypocrisy of the San Fransisco police department’s targeted attacks on street youth. Police “sweeps” were routinely performed on the streets of the Tenderloin. Trans women were especially vulnerable, and could be arrested at any moment. When they finally reached city jail, they were treated to a ritual of humiliation that started with a strip search and ended with a head shaving.

Vanguard youth took a multi-prong approach with their own “clean sweep”, not only protesting the brutality of law enforcement in the area, but also literally cleaning the filth that was thrown into the streets by the middle-class businessmen that flocked to the area for sex.

“We’re considered trash by much of society, and we wanted to show the rest of society that we want to work and can work.” - J.P Marat, President of Vanguard - Issue 2, circa 1966

“People were being killed, beaten, stabbed, robbed, denied their rights. Fired. Un-hirable. On the other hand there was an awful lot of celebration. And a lot of caring and taking care of each other.” - Keith, Oral history with Joey Plaster

Gene Comptons Cafeteria was one of the few public spaces that offered a degree of safety for the disenfranchised that called the Tenderloin home. The 24-hour diner was located at a central spot in the district, offering cheap food in a clean environment. Described as existing in a magical dimension similar to Oz, drag queens and trans women could be seen kiki-ing in their closet’s most glamorous finery as they drank coffee, smoked cigarettes, and dined on toast and eggs. Still, the diner was routinely raided, and queer patrons did not receive equal treatment to their straight counterparts.

Members of Vanguard were also frequent patrons of Compton’s. The aura of new-found empowerment that encircled the homeless youth began ruffling the feathers of the diner’s management, and members were now met with an even deeper sentiment of unwelcoming hostility.

In true Vanguard fashion, this called for… a picket! On July 18th 1966, 25 members gathered outside of the restaurant with signs that read “Drag Out In The Open”. The picket set the stage for a riot that became the first instance of collective militant queer resistance against the police in America’s history — three years before the first brick flew at Stonewall.

“For nineteen cents you’d have a hamburger, but you weren’t allowed to eat there, and the manager would yell at you, saying ‘Faggot, eat your hamburger outside.’ You’ve lost everything, you’ve lost your family, you may have lost your boyfriend — cause he OD’d — you may have lost your freedom, being busted for petty crimes, and you can’t even eat a damn hamburger? It just really got to me… My friends overdosing, and not even being able to eat a goddamn hamburger in a sleaze joint.” - Joel Roberts, Oral history with Joey Plaster, circa 2010

One month after the Vanguard picket, on a night in August 1966, police walked into the florescent glow of Compton’s to conduct a raid. When a cop grabbed the arm of one of the seated queens, a landmark moment came to fruition. With nothing to lose, she turned, and instead of submitting to the officer, wrapped her painted nails around a ceramic mug and splashed coffee in his face. This simple act of resistance was all it took to ignite the diner into a full blown riot. Compton’s erupted, and the patrons began flipping tables and throwing anything they could get their hands on at the police. Sugar shakers flew through glass, hustlers kicked and punched the officers, and the queens beat the cops with their heavy purses and heels.

The mob ran the police out into the streets, continuing to beat them back as the paddy wagons sped around the corner of the block. Before the fight was over a police car was destroyed, a corner news stand was set on fire, and the event was stamped as the first recorded act of queer resistance to police harassment in American history.

“I felt that it was a liberation, it felt like gay liberation. At that point it freed us to be ourselves, not to be afraid, not to be ashamed. It was a whole new day. It felt totally different. It was like we had transcended, we had reached the top of the hill and we were now coming down the other side.” - Adrian Ravarour, circa 2011

“Perhaps I have seen the other prophets in the faces of some of the young people who live and hustle in the Tenderloin. They are the ones who have exhibited a kind of compassion which you and I are afraid to show. They have allowed as many as eight or more homeless hustlers of Market Street to sleep on their floors and to share their meals. Some of them speak, even in their personal loneliness, of a love that overcomes the barriers that have placed them in society’s garbage can.” - Glide Methodist Intern Larry Mamiya, circa 1967

By 1967, Vanguard had achieved much of what they had sought out to accomplish. Through their magazine, pickets, and community outreach they brought attention to issues of poverty, police harassment, loneliness, drug abuse, sex work, violence, the war in Vietnam, suicide, sexuality, gender expression, the power of community, political action, and queer theology.

Because of their effective community outreach, they were able to successfully leverage funds that had been made available through the War on Poverty, and the Tenderloin became the first district to be funded due to discrimination based on sexual orientation. Vanguard president Jean-Paul Marat and advisor Mark Forrester were appointed aids, and in 1967 their office funded the nations first transgender organization (Conversion Our Goal), the first urban mobile health unit, and a 24-hour drop-in service center for runaways and street youth that is still in operation today. (The Hospitality House).

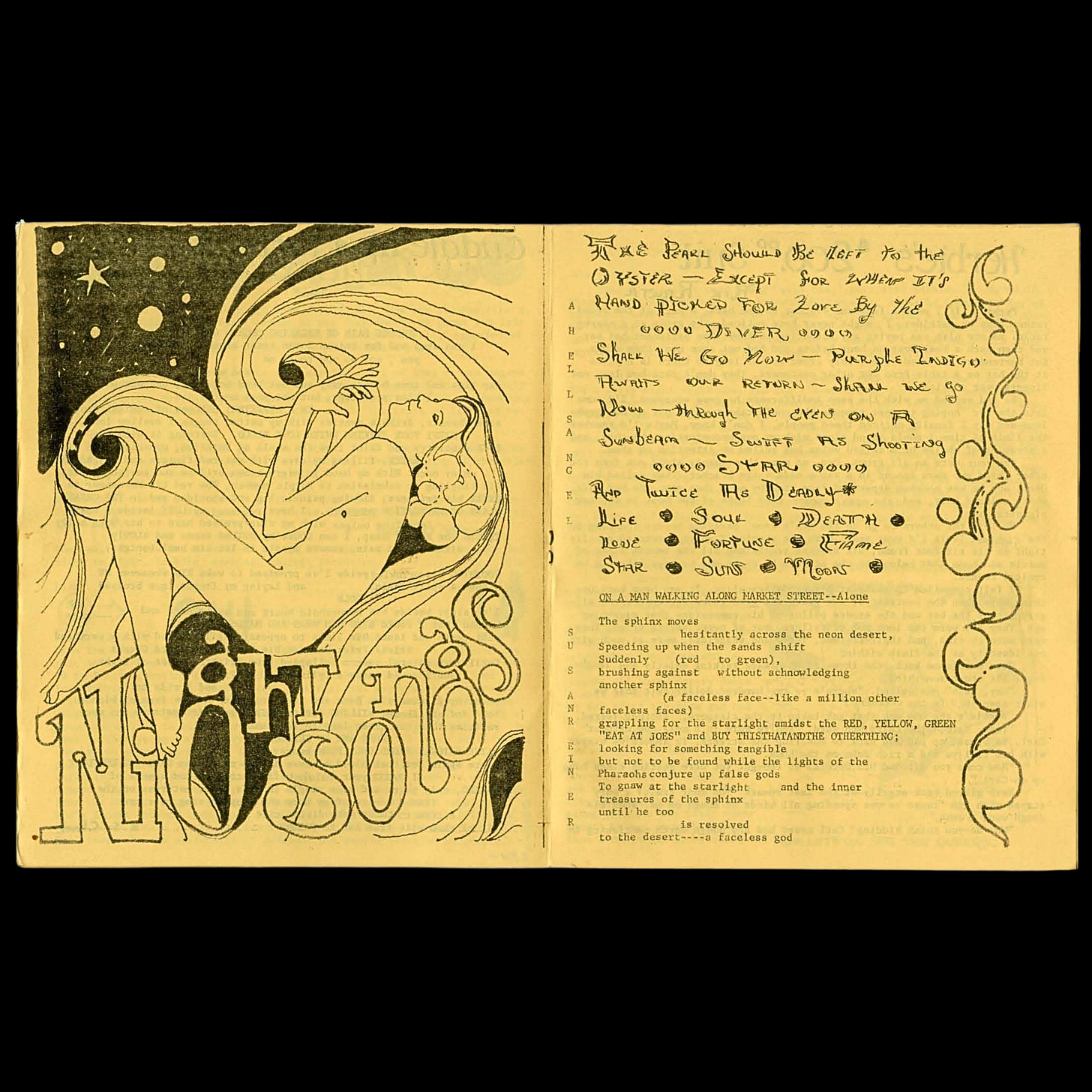

Though the year saw Vanguard dissolve as an organization, the magazine continued it’s publication through the 1970s. For several years it was published out of 330 Grove in the Haight, which served as a community center that also housed the Angels of Light and the Black Panthers.

“The message of Vanguard is LOVE. You know when you are isolated…if you can’t love then it builds up a certain amount of anguish, sometimes hostility. If you can’t love somebody freely then you don’t feel free, so you want to do something that you’re free to do. The longing for love seems to break out into typist fingers. It seems to break out in song, in verse. Submitting your written work freely to a free magazine is one free thing you can do. And that’s what they did.” - Keith, Oral history with Joey Plaster

Hope, resilience, courage, and most of all — love. These are the lessons we take from our Vanguards.

The queens who let it be known they not only had a right to exist, but to parade their beauty without fear.

The pastors who welcomed queerness as a gift from God, one that was always meant to be celebrated.

The hustlers who used the streets as a stage, casting a light on injustice that was so bright, witnesses had no choice but to see.

If you’re feeling curious and would like to learn more, I highly suggest exploring the collection of Vanguard Magazine housed on the Transgender Digital Archives website, and watching the documentary Screaming Queens, which provides a host of high quality archival footage and images, and tells the story of the Compton Cafeteria Riot via first hand accounts.

These essays are a labor of love, and require many hours actively researching, writing, and compiling images/source material. If you enjoy my work, becoming a paid subscriber is the best way to support me so I can continue to publish!

Thank you for being here!

<3 Kari

February’s Keepers

A collection of thirty vintage pieces to get you through winter’s final blows. Mohair, down, suede, corduroy, wool and faux fur make for an inviting mix as we wait for the daffodils.

Sources:

Digital Transgender Archive: Vanguard Collection

Vanguard Then and Now: An Evolution of Gay Youth Activism in the Tenderloin

Screaming Queens | KQED Truly CA

“A ‘Secularized’ Church Pursues Its Mission In Unorthodox Causes

thank u for putting the work into researching, compiling images, and writing this. this radical history is so important to learn & hold onto as fascism intensifies.

What an incredible post! I learned so much. Thank you for taking the time to research and put this together!