The Victorian Era

Though they are now synonymous with “it-girls” of the 2020s, “bloomers” got their start as political weapons. American feminist and early suffragette Amelia Bloomer wrote an article in the April 1851 edition of her newspaper The Lily, the first US newspaper to be edited by and for women, that opened the conversation of women’s dress in a way that had never been done before. The essay included a print of herself wearing a daring outfit that layered a pair of “pantaloons” underneath a knee length skirt - offering it as a comfortable alternative to corseted and heavy petticoated layers that upper and middle class women were accustomed to at the time.

“As soon as it became known that I was wearing the new dress, letters came pouring in upon me by hundreds from women all over the country making inquiries about the dress and asking for patterns—showing how ready and anxious women were to throw off the burden of long, heavy skirts.” - Amelia Bloomer.

As interest in the style grew, women who adopted the trend became known as “Bloomerites”, practitioners of “Bloomerism,” or wearing “bloomers”. Naturally, this rejection of societal norms caused Bloomerites to be greeted with harassment from the press, who printed unflattering political cartoons that focused more on what early suffragettes were wearing rather than the issues they were raising, causing them to dust off their corsets and petticoats for a return to the more “acceptable” silhouette.

Black feminists of the Victorian era did not have the same experience experimenting with radicalized dressing. Abolitionist and suffragette Sojourner Truth had been forced to wear pants while she was enslaved, and saw the act of wearing a dress as a symbolic reclaiming of the womanhood that her enslavers had attempted to take from her. Her blackness carried an association with racist stereotypes of the time that saw her as angry, promiscuous, aggressive, and in direct violation of social norms. Wearing what was seen as “presentable” was a necessary step for her safety, and in many ways was a radicalized act.

During the Civil War, women who remained home found themselves able to move upwardly in ways that were not possible prior. While their male counterparts filled battlefields, many of these women took on management of farms and shops or embarked on business ventures. Some left home all together to serve as nurses, writers, and spies on the front lines. Being a time when most women sewed their own clothing, they armed themselves with needle and thread to express their patriotism. They made quilts, aprons, and uniforms - with the United States even providing a pattern for a Union soldiers costume.

In 1861, my ancestor, twenty year old Mary Ellen Himes-Fox of New Bethlehem Pennsylvania, created this apron as an act of solidarity with her husband, brothers, and cousins who participated in the war as Union soldiers - it’s stars representing each the 34 states. Evidence on the apron suggests it was only worn once, as it’s bib contains a single set of pin holes. It is now housed at the Gettysburg Museum.

The Edwardian Era

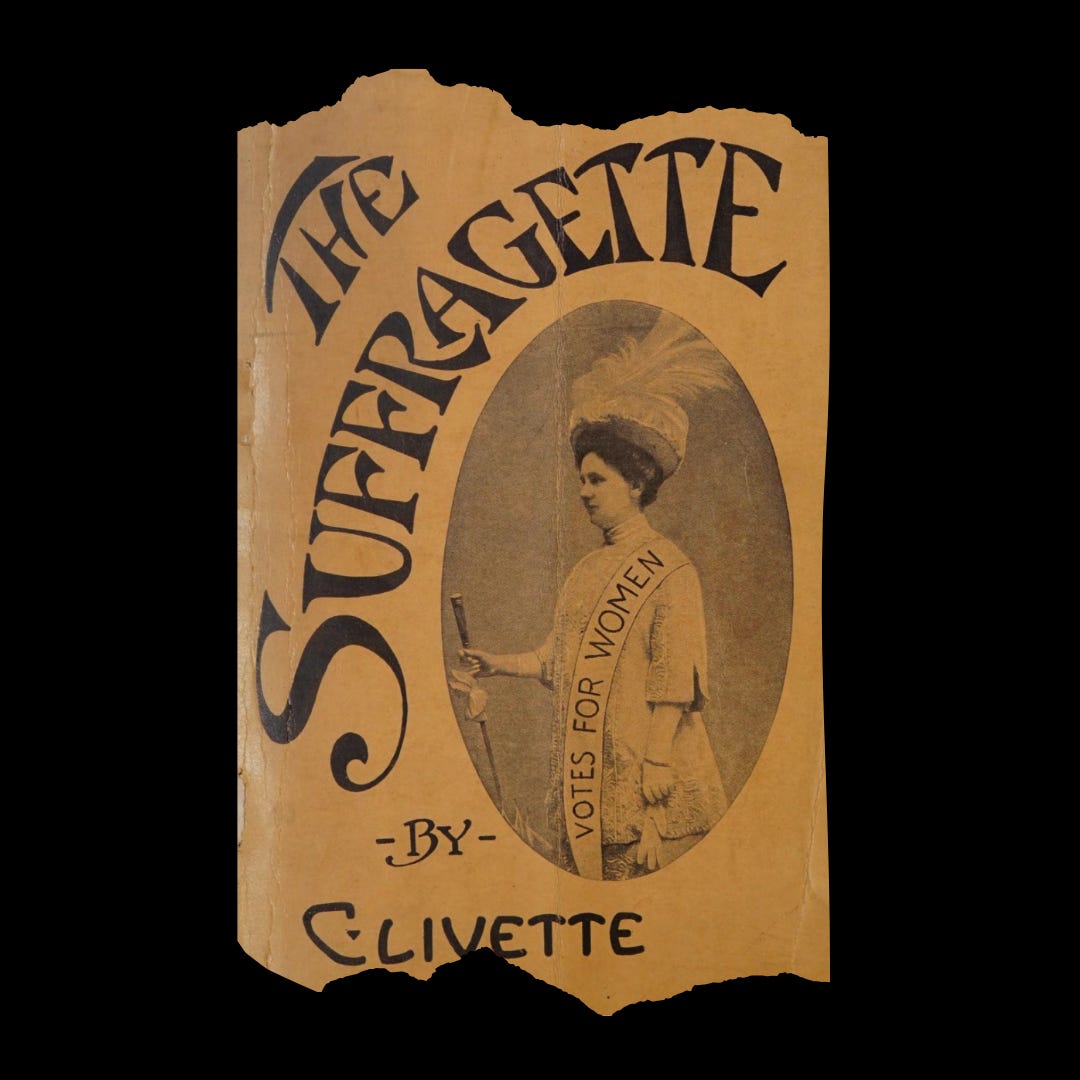

As the Suffragette Movement progressed into the 20th century, women adopted the use of color to signify belief systems. White, yellow, and purple became representative of purity, hope, and loyalty to the cause. These colors were chosen specifically for their accessibility. Women of the time could piece together outfits from their existing wardrobes and move from their bedrooms to the streets with ease.

Ready made and mass produced clothing was in its infancy, and the popularity and affordability of white dresses allowed suffragettes to easily use the color to recruit and promote the cause. In 1917, black activists in NYC marched down Fifth Avenue in a silent protest against lynching and racial discrimination. The sea of white linens did more than signal suffrage, the dresses spoke directly against the racism black women endured from a white society. It showed that they were as pure, respectable, and moral as their white peers - something many white suffragettes did not believe at the time.

White women gained the right to vote with the passing of the 19th Amendment in 1919, while black women had to wait until 1965 to achieve full access to the same privilege.

The War Years

As the mass production of ready made clothing progressed through the 1920s and into the 1930s, many women had lost touch with their sewing kits and knitting needles. By the late thirties only 50% of women knew how to sew. By 1944, around 82% of women in America were practicing the skill. This significant increase was due to the formation of sewing centers across the country that were a direct response to fabric rationing during WWII. Women took classes on reusing clothing and fabric remnants to create new garments for themselves.

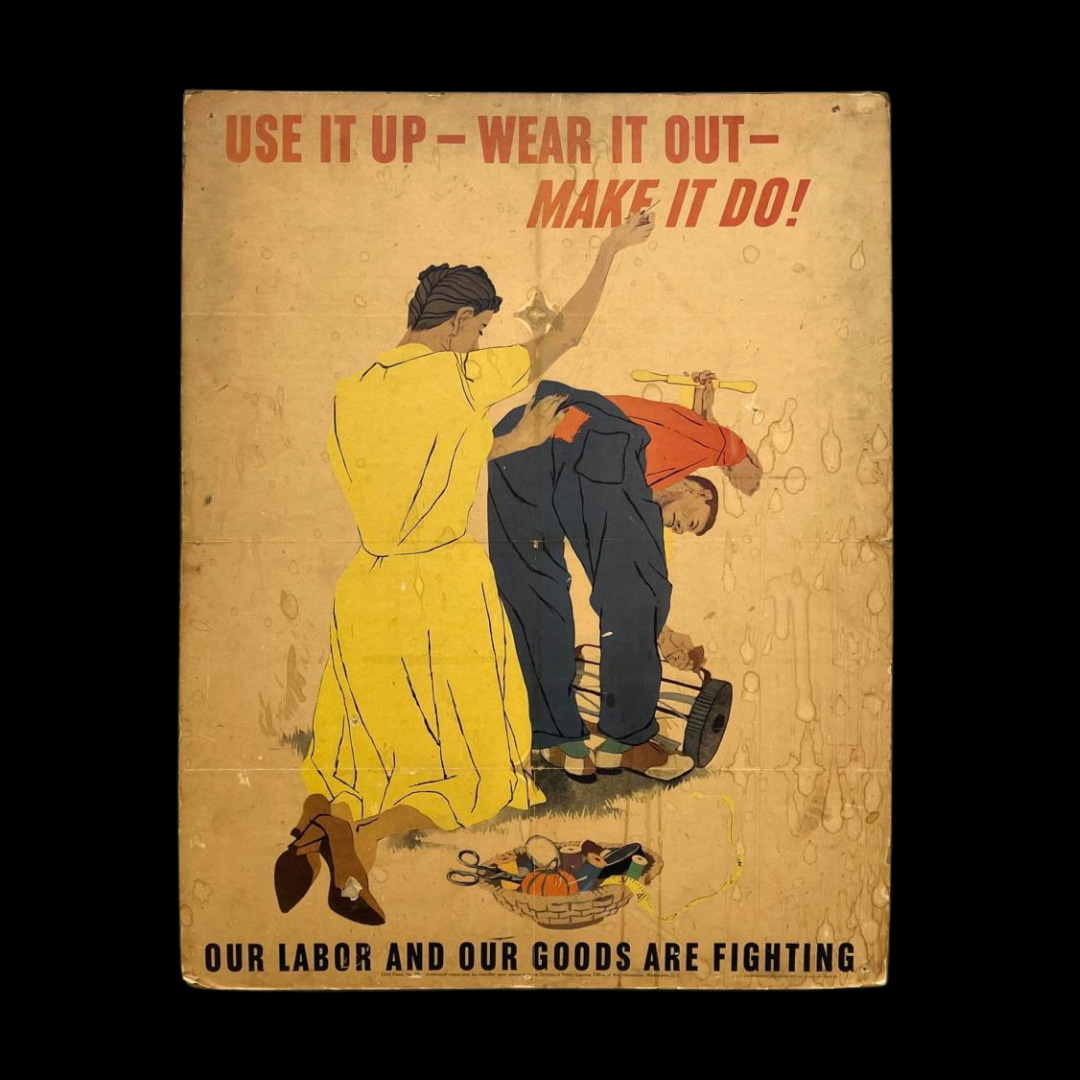

Posters soon began circulating that encouraged women to “Use It Up - Wear It Out - Make It Do!” and to “Sew for Victory” by volunteering at makeshift Red Cross factories that had begun popping up in office buildings, libraries, and churches across the country. In these factories women sewed beanies, bedspreads, duffle bags, pajamas, bed jackets, Army kit bags, helmets, Navy sweaters, mufflers and a myriad of other garments that helped support the war effort overseas.

Recycling, patching, and mending old clothes was soon adopted as more than a need for the thrifty, it was a trend that visibly showed a woman’s patriotism and loyalty to the war effort.

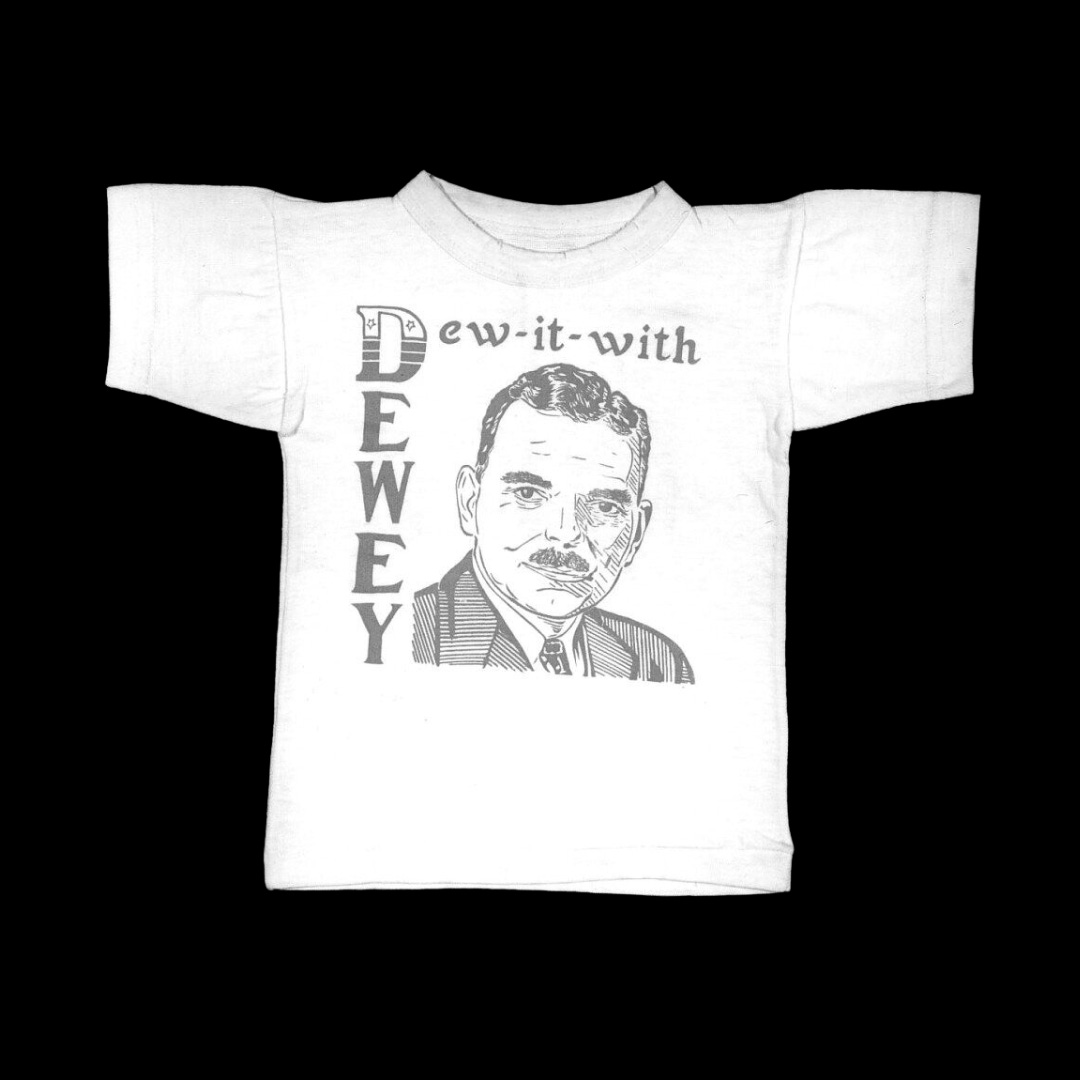

The 1940s also saw the first known example of a political tee shirt, with New York governor Thomas E.Dewey’ printing a tee that read “Dew it with Dewey” for his 1948 presidential campaign.

The Fifties

During Dwight Eisenhower’s 1956 presidential campaign, thousands of “Ike Girls” donned silk screened dresses in support of his re-election. The dresses featured the popular Dior “New Look” silhouette and kept with the feminine ideal of the time - a cinched waist and a full skirt. These Ike Girls were significant in appealing to female voters, handing out buttons and leaflets and engaging in political campaigning for the Republican.

His supporters were not limited to upper class white women, with many women of color and women of varying income brackets backing his re-election. His broad appeal with women was credited to his campaigning for desegregation, labor and union laws, and preservation of Social Security.

The Sixties

The sixties saw an explosion of fashion used as a medium for subversion, rebellion, identity, and expression - so it is no surprise that various political movements took advantage of the power of dress. Presidential candidates Nixon and Kennedy jumped on the trend of disposable paper dresses to help promote their campaigns to young voters.

Famously, The Black Panther party became synonymous with have an intentional and recognizable all black uniform. They wore Afros and wore their hair natural as a rejection of Eurocentric beauty standards, berets sat atop their heads a historic symbol of militant resistance, sunglasses protected their identities from FBI surveillance, and buttons and patches helped further promote their cause with slogans such as “All Power to the People”. Firearms often topped the outfit off, though not all Panthers wore them, and they were used to protect members of the black community from police brutality.

“We use the Black Panther as our symbol because the nature of a panther. The panther doesn't strike anyone, but when he's assailed upon, he'll back up first. But, if the aggressor continues, then he'll strike out.” - Huey P. Newton, Black Panther Founder.

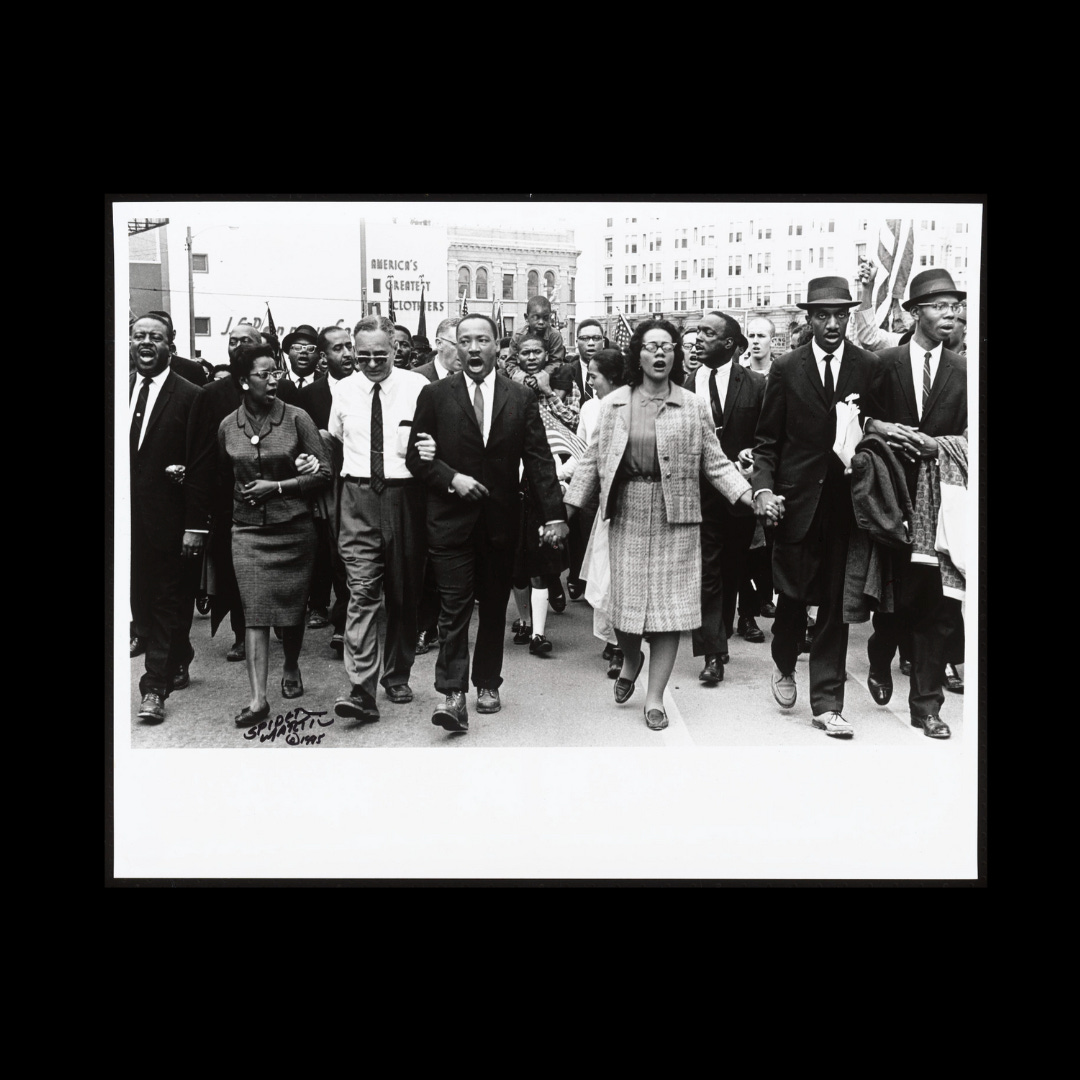

On the other side of the coin, Civil Rights Movement leaders such as Dr. Marten Luther and Coretta Scott King wore '“Sunday Best” when protesting in the streets. They believed that suits, dresses, and well groomed hair demanded the white public to treat them with dignity and respect. This ideology reframed the idea of what a protestor looked like, similarly to what was done by black suffragettes in the early 1900s.

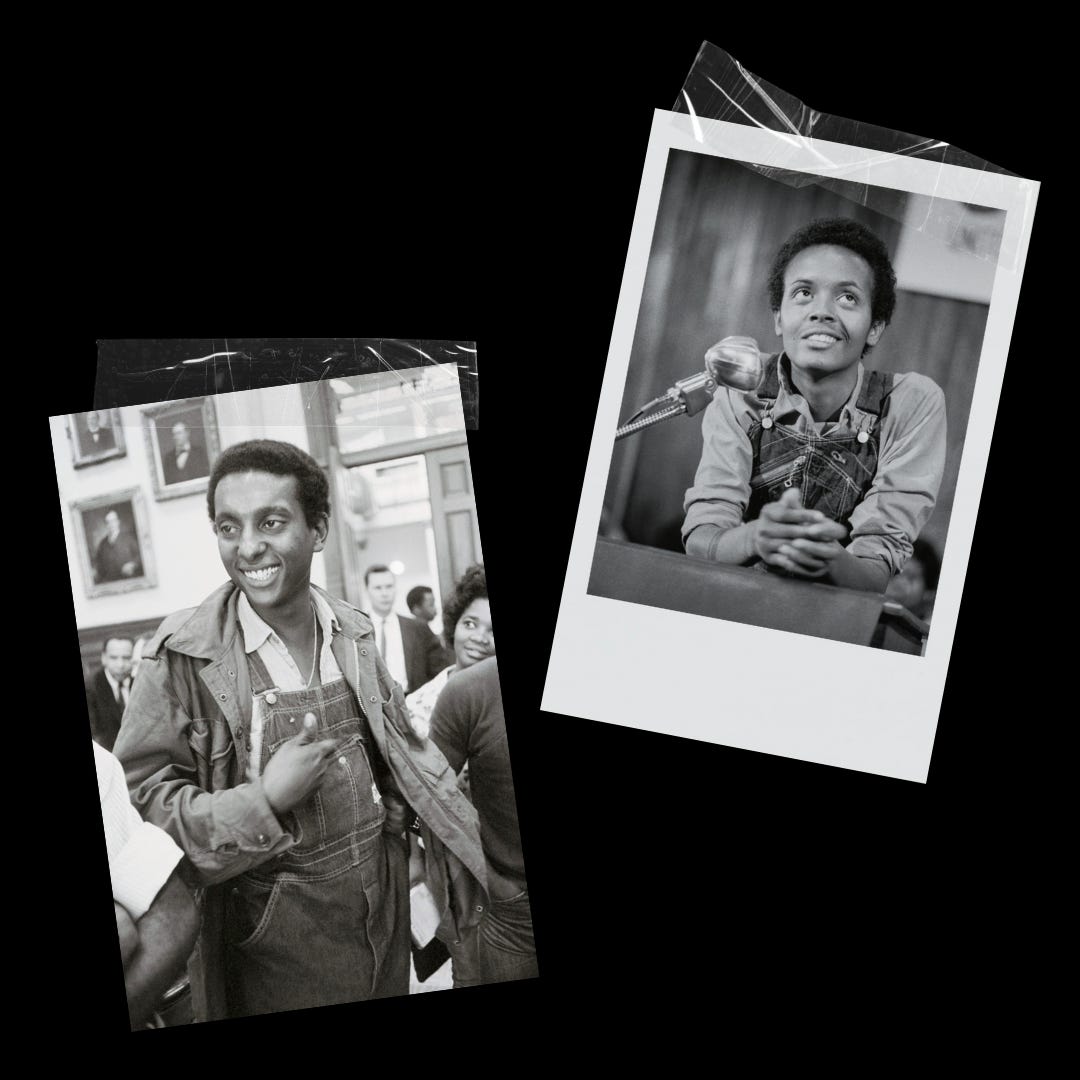

Many young activists at the time did not care what white citizens thought about them, and rejected the idea of Sunday Best all together. Instead they chose to use blue jeans and overalls as a symbol of resistance. These traditional working class garments harkened to images of poor rural sharecroppers, and were used as a dramatic representation of how little had been accomplished since the Reconstruction.

Overalls offered practicality for the wearers, as they helped protect against the dog attacks and high pressure hoses that were frequently used by police on black protestors. Denim also allowed individuals to present themselves in a gender neutral fashion, serving as a way to visually level the playing field between men and women involved, with activists like Joyce Ladner and Stockely Carmichael donning the same uniform. As denim became synonymous with the struggle for civil rights, its nonconformist message was co-opted by white American youth culture.

The Seventies

“Old enough to fight, old enough to vote.” This rally cry came from a teenage generation that had endured the horrors of the Vietnam war, but were unable to cast a ballot on home soil. The movement of young people advocating to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 led to the ratification of the 26th Amendment in 1970.

The 1972 presidential campaign marked the first time that Americans 18-20 were able to cast their ballots for the candidate in the favor. The Student Vote Project worked on getting the word out on popular radio stations and released a youth centered line of clothing and accessories designed to make voting something to proudly display. Purses, tee shirts, buttons, pants, sneakers and even umbrellas boldly displayed the word “VOTE”.

The 1970s showed us the power of the tee shirt, seeing the birth of tees used for politicians and causes. Anyone who had access to a cheap blank tee and a silk screen was able to print a message that promoted their beliefs to the world.

Tee shirts were used by the environmentalist movement to save the whales, promote clean air and water, and protest nuclear energy. They were used by queer rights activist to encourage pride, campaign for gay candidates such a Harvey Milk, and promote queer businesses and organizations. They were used by feminists to rally against violence, celebrate women, and protest anti-women’s rights legislation. They were used by civil rights activists to boost leaders who were fighting for equality.

The humble tee shirt continues to be one of the most effective and frequently used ways to spread our political ideas with the world, with many of these vintage tees still remaining in circulation for new generations to use as political signifiers.

As we look back through history, what may seem mundane in our wardrobes — denim, the color white, berets, or even pants - often has a much deeper significance that can be transmuted and applied to the political climate we experience today. Our right to vote was secured by centuries of hard work from women, queers, and people of color who risked it all to ensure future generations had a say in who made decisions about their lives. Don’t let all their hard work go in vein, please vote - and do it in style!

More like this…

Sources

The History of the Color White and Women's Suffrage Movement

Popular and Pervasive Stereotypes of African Americans

Different Ways Clothing is Used to Signal Politics Throughout U.S. History

Breaking Down Boundaries: Women of the Civil War

A Brief History of the T-Shirt

How Denim Became a Political Symbol of the 1960s

“Sew for Victory!” How Women During World War II Used Their Domesticity to Aid the Cause

These groovy duds encouraged the youth vote after the 26th Amendment